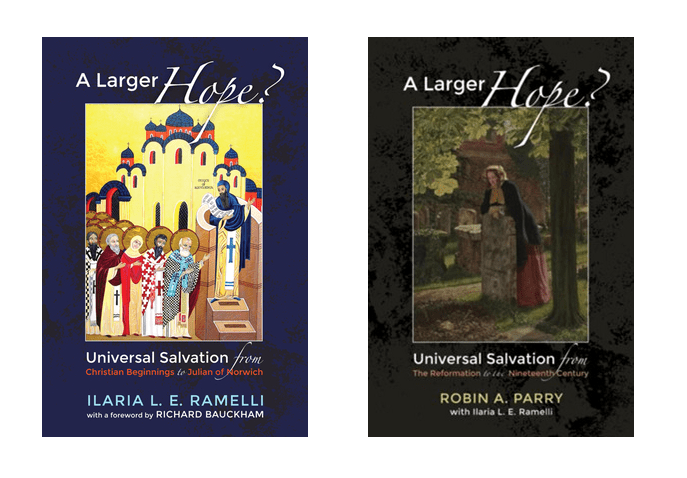

A LARGER HOPE? Universal Salvation from Christian Beginnings to Julian of Norwich (Volume 1), Ilaria L. E. Ramelli, forward by Richard Bauckham, 2019, Eugene, OR, Cascade Books, 286 pages including Preface, two appendices, and bibliography. ISBN: 978-1-61097-884-2.

A LARGER HOPE? Universal Salvation from The Reformation to the Nineteenth Century (Volume 2),Robin A. Parry with Ilaria L. E. Ramelli, 2019, Eugene, OR, Cascade Books, 313 pages including appendix, bibliography, and index of names.

I embraced, to use Robin Parry’s words, the “perennial heresy (V.2, p.269)” a long time ago. Long before its popular resurgence in recent years. Long before Rob Bell, David Bentley Hart, Robin Parry, and long before Michael J. McClymond felt the need to call it the “opiate of the theologians (Christianity Today, 3/22/19)” and write his epic rebuttal of Christian Universalism, The Devil’s Redemption (2018). And long before Ilaria L.E. Ramelli and Robin A Parry’s epic history of universal salvation.

If you will indulge me a bit longer, I arrived at Christian Universalism in an uncommon way, through Celtic Christianity, and subsequently, John Scotus Eriugena and his fellow Celtic Latins. Along the way I fell in love with the Desert Fathers, in particular, St. Anthony, whom the Celtic hermit-monks sought to emulate. As early Celtic Christianity gravitated more toward the Eastern Church than Roman Church, I began to read the works of Gregory of Nyssa. From there is was a short trip “backwards” to Origen and apokatastasis.

We had looked at Origen’s apokatastasis in seminary, but being it was an Evangelical seminary with Reformed leanings, it was dismissed as unscriptural. I wish now that Ramelli’s seminal work on apokatastasis, a thousand-page monograph, was available then, or later when I embraced Christian Universalism (The Christian Doctrine of Apokatastasis: A Critical Assessment from the New Testament to Eriugena, Brill, 2013).

Even if it were, I couldn’t afford to buy it. So, I was quite excited to learn that Ramelli had written a new work, A Larger Hope? In which she summarized her previous work. When the opportunity came along to review the work, I jumped at it.

Ilaria Ramelli’s work, A Larger Hope? Universal Salvation from Christian Beginnings to Julian of Norwich is volume 1 of a two -volume work. The volume, written by Robin A. Parry covers “Universal Salvation from The Reformation to the Nineteenth Century.” There is also a projected third volume covering twentieth and twenty-first century Christian Universalists and their theologies of universal salvation.

Both volumes of A Larger Hope should be read by anyone who professes universal salvation. They should be required reading for all who minister under the broad umbrella of Christian Universalism. I would go even a step further and suggest that both volumes of A Larger Hope? be read in conjunction with McClymond’s The Devil’s Advocate. It would be fantastic, I think, if both were required reading in seminary.

Origen’s apokatastasis is the crucial root of universal salvation and as such needs to be understood. Origen may be the “Father of Universal Salvation,” however as Ramelli shows, the concept universal salvation, or apokatastasis, is not foreign to the scriptures or to the early Christians. Nor did the concept remain in obscurity after Origen.

Robin Parry says, these volumes are not so much as history as they are a tale—a tale that needs to be told. A tale that weaves itself through Christian history. A tale that sometimes takes odd jaunts. Volume 2 is full of such jaunts. More importantly, it is a tale that demonstrates that the concept of universal salvation is not a “perennial heresy” that keeps popping up, but an orthodox strain of Christianity that has been present from the beginning.

McClymond challenges the orthodoxy in his work, claiming that Origen’s apokatastasis has roots in pagan, Gnostic thinking that he embedded in his theology, and that Ramelli glosses over Origen’s Gnosticism. Ramelli aptly dispels both of McClymond’s claims. [A detailed rebuttal to McClymond is found in Volume 1, Appendix II, “Is Apokatastasis ‘Gnostic’ Rather than Christian?”]

In The Devil’s Advocate, McClymond claims that more recent Christian Universalism is full of the esoteric, metaphysical thinking of Jakob Bhme (1625-1724). This claim is put to rest by Parry (Vol. 2, Chap. 4) [McClymond’s charge is directly addressed in Appendix I, Volume 2, “Is Jakob Bhme the Father of Modern Universalism?”]

Although not written as a theological rebuttal of those who claim universal salvation is unscriptural, both volumes of A Larger Hope demonstrate how wrong such thinking is. It was until the time Augustine that the claim of universal salvation being unscriptural became mainstream. Ironically, prior to his tiff with Origen theology, Augustine embraced universal salvation: “That “God’s goodness [De bonitas] … orders all creatures [omnia] that have fallen … until they return to the original state from which they fell (De mor 2:7:9) (p. 156).” Very much, Origen universal salvation.

As Ramelli tells it, Augustine became obsessed with rebutting Pelagianism, which he considered to be a heresy. Misunderstanding Origen as Gnostic, he found the roots Pelagianism in Origen. And if Origen was Gnostic, then nothing good could come from him. Add to that, Augustine had little, if any, working knowledge of Greek, which in turn caused him to misunderstand the meaning of ““aeternus fire.” In the Latin Vulgate it is “eternal – forever – fire.” In Greek it can mean “other-worldly” and “long-lasting.” [The meaning of Ainios is explored in Volume 1, Appendix I.]

It is insights such as these that make Volume 1 essential reading. I do wish however, as Eriugena and the Celtic Latins were part of my journey, that Ramelli had spent more time with them. Considering the scope of her work, a minor quibble for sure.

I found A Larger Hope? Universal Salvation from Christian Beginnings to Julian of Norwich (Volume 1) not only to be informative; as I read, I also found it strengthening my belief in Christian Universalism. On the other hand, Robin Parry’s contribution, A Larger Hope? Universal Salvation from The Reformation to the Nineteenth Century (Volume 2), became for me a footnote to my journey into Christian Universalism.

Reading Parry’s extensive catalog of those who held to Christian Universalism I discovered hereto unrecognized influences on my journey (such as Hannah Whitehall Smith, Charles Chauncy, George MacDonald), as well those with whose thinking I am quite comfortable. Without his Unitarian bent, I am quite comfortable with Hosea Ballou’s idea that Christ’s work on the cross was about our orientation toward, and reconciliation to, God. I am as comfortable with the Winchester Confession as I am with the Nicene Creed. I could probably fit quite well into the old Christian Universalist Church of America before it drifted into Unitarianism.

With his list of characters – and an interesting bunch they are – Parry shares the thinking of the well-known and little-known. I appreciate his shining the light into the dark corners Christian Universalism. Among those covered are Evangelicals and Liberals. There are those who would be labeled “orthodox” or “heretic.” There are Calvinists, Arminians, Pietists, and Charismatics, Trinitarians and Unitarians. There are those who view Christ’s work on the cross as substitutionary salvation, and there are those who view it differently. There are those who believe in some sort of potential remediation after death, and those who hold no stock in such remediation. We Christian Universalists are quite a colorful, diverse bunch.

All of these folk, along with the Origen, and the Patristic theologians, have contributed one way or another to our contemporary twenty-first century Christian Universalism. I urge you to read, not scan, find your own Christian Universalist roots, reenforce them, figure out (and defend) why you are not another sort of Christian Universalist. I think you will be glad you did. I know I am.

Ending on a personal note: Thank you Robin for helping me discover both unrecognized influences and my place within Christian Universalism. Thank you Ilaria for affording me an opportunity grow my Christian Universalistic roots back to the early Church. Because of both of you, and your epic contribution to Christian Universalism, my faith in universal salvation is stronger.

I am looking forward to Volume 3.

Just one suggestion: The inclusion of an index in the next edition of Volume would, I think, be helpful.

Ilaria L. E. Ramelli is Professor of Theology and K. Britt Chair in Christology at Sacred Heart in the Graduate School of Theology, Angelicum University.

Robin A. Parry is a curate at the Church of St. Martin with St. Peter in Worcester, UK, and an editor for Wipf & Stock Publishers. He is the author of The Evangelical Universalist, written under the pen name, Gregory MacDonald, Eugene, OR/London: Cascade Books/SPCK (2006).

A quick note: Both these books are already part, of the CU portion, of CUA Church History course.

–your CUA office staff

I have both these books and they are exhaustive and very well written

all universalist scholars need a copy in their libraries.